Early

Days

Perhaps in 1959

1. According to what I was told during a visit to my Mum and Dad in

1997:[i] “It was in 1959 that Dad got the first motorbike and sidecar; and it was only a few months afterwards that he got the second one with the

Busmar sidecar.” How many months “a few” were, I’m not certain; my impression is that we had the first vehicle for several months, not just a few. My Dad had a driving licence for a motorcycle but not a car, so a motorcycle-sidecar combination was the only way to provide transport for the four of us

together:[ii] Mum, Dad, our Steve, and me. Typically, Steve would ride pillion behind my Dad, and Mum and I would occupy the sidecar.

- [i] Thursday 5th June 1997

[ii] Not, in fact, “the only way”; perhaps I should have written “the only affordable way”: there were three-wheeled cars manufactured by the Reliant Motor Company; as a three-wheeled vehicle of lightweight construction (under 7 cwt), under UK law it was considered a “tricycle” and could be driven by holders of a motorcycle licence. My Dad got his first Reliant in November 1965 (see

Friday 25 February

1966).

Visits to relatives and others

Nanny Paine and Grandad Jack, and others

2. We would use it to visit relatives locally — Nanny Paine and Grandad Jack (my Mum’s mum and dad) at 91 Watson Road, South Shore, Blackpool, for example; also others in South Shore: Auntie Edith and Uncle Albert (actually, my Dad’s aunt and uncle; but still called “auntie” and “uncle” by Steven and me) at the Pleasure Beach end of Watson Road; or my Dad’s cousin David and his wife Eileen, in a house off Watson Road between the two (we may have referred to them as “uncle” and “auntie” as well).

Before we had the motorbike and sidecar, it was a journey of two buses to go there, and of course a further two to come back: a №14 or №14A bus to Talbot Road Bus Station; then — was it a №22 from there to Watson Road? The destination, shown on the indicator panel next to the one displaying “22”, was “Halfway House”; but since we got off before it, I never knew what or where that was. These were cream-and-green liveried Blackpool Corporation Transport buses; but at the bus station we could also get a dark blue-and-white Lytham St.

Annes[iii] Corporation bus №11.

“The destination, shown on the indicator panel next to the one displaying ‘22’, was ‘Halfway House’; but since we got off before it, I never knew what or where that was.” (Painting by G. S. Cooper, retrieved from

www.cooperline.com)

“We could also get a dark blue-and-white Lytham St. Annes Corporation bus №11.”

- [iii] “St Anne’s” is spelled with an apostrophe on Ordnance Survey maps, and indeed by Fylde Council, of which borough it has been a part since 1974; but on the sides of buses it was spelled without: “St.

Annes”.

Auntie Margaret and Uncle Ronnie

3. The environs of Watson Road were some 6½ or 7 miles distant by the motorbike and sidecar, depending on the route we took; but closer to home, there were Uncle Ronnie and Auntie Margaret in Little Carleton (50 Kendal Avenue), 2½ miles away. Uncle Ronnie was my Mum’s younger brother. I remember, too, visits there by bus. It was the same bus as we’d catch to go into Blackpool, the №14 or №14A; but we’d get off in Blackpool Old Road towards its end, at the Poulton Old Road bus stop, cross the road, and walk down the ginnel that would take us directly to the house, a semi-detached on the corner of Kendal Avenue and Burnsall Avenue. That was the context in which I first heard the dialect word

“ginnel”.[iv] Their house always impressed me as being spotlessly clean, with paintwork all bright and shiny as if it had only just been

painted.[v]

- [iv] It was my Mum from whom I heard the word “ginnel” /ˈgɪn(ə)l/. She came from Blackpool. I never heard my Dad say it. He came from Sheffield; and when I met my cousin Mary there in 1967 and said it, she told me that they used the word “gennel” /ˈdʒɛn(ə)l/.

“We’d get off in Blackpool Old Road towards its end, at the Poulton Old Road bus stop, cross the road, and walk down the ginnel that would take us directly to the house.”

Image from Google Maps in 3D view, imagery © 2018 Google, map data © 2018 Google

The ginnel runs between the two houses on the right.

Image from Google Street View, image capture Sep. 2018 © 2018 Google

[v] I think this impression, contrasting with that of our house, stems, not from the latter’s being in any way less clean, but from the fact that my Dad made built-in cupboards and shelves, which were competently enough constructed, but only adequate in appearance, not perfect.

Auntie Sally and Uncle Jack

4. Or we might visit Auntie Sally and Uncle Jack (Mum’s older brother). They always seemed to be moving house; Auntie Sally was restless, or perhaps she fell out with the neighbours. But I remember visiting them when they lived in Lakeway, off Newton Drive at its east end. I associate that area with visits to the fish-and-chip shop (“Senior’s”) at Staining Road End; so it could be that we would go for our dinner there — that’s what others might call “lunch” — a sit-down dinner in the café behind the shop, then go to visit Auntie Sally and Uncle Jack, a little less than a mile away, before going home. Or we might go at tea-time (“dinner” for those who called dinner “lunch”). (What day would this be? It’s unlikely to be Saturday, for on Saturdays our Steve and I would have dinner and tea at Nanny Cooper’s, a short walk away from our house.)

Auntie Joan and Uncle John

5. Not far from the west end of Newton Drive lived Auntie Joan and Uncle John, and their children Graham and Frances, who were about our Steve’s and my age, respectively. There’s no association in my mind, though, between that location and where I’ve just mentioned; indeed, it was a surprise to me to realise later on that it was the same Newton Drive, from which Lakeway branched, as that where Joan and John McIvor lived. Joan and John weren’t really our aunt and uncle, we just called them that; I think they were part of the “gang” that my Mum and Dad used to hang around with about the time of the outbreak of the Second World War. He was from Scotland, and I could barely tell what he said when he spoke. There was also a deaf old white-haired granny who sat in the corner. Anyway, we would visit them from time to time.

Auntie Connie and Uncle Roland

6. And there were Auntie Connie and Uncle Roland, and their adopted little daughter

Lisa.[vi] (Later they had a natural daughter, Judy.) Roland and Connie Gray too were just called “Uncle” and “Auntie”, but weren’t related; they also were part of the “gang”. They were our Steven’s godparents. They had a radiogram, which played music of higher quality than I’d heard hitherto; and they had a number of long-playing records by Mario Lanza,

e.g. The Great Caruso and The Student Prince. I don’t think my parents, or just my Mum perhaps, shared the Grays’ enthusiasm for Lanza. He sounded all right to me, though: better than all right.

Alcoholic drinks would be forthcoming, and I would be permitted sometimes to have a “taste”. Port was decidedly more to my liking than sherry, because it was sweet. Whisky tasted intolerably nasty. That calls to mind doing a whole round of visits before Christmas, for the exchange of presents, when a drink would be offered my Mum and Dad at every place we visited. One wonders whether my Dad was in a wholly fit state to drive us

home.[vii]

- [vi] Steven and I used to get Christmas presents from “Auntie Connie, Uncle Roland and Lisa”; strangely, my present for Christmas 1960 was inscribed as just from Lisa:

To John

with love & best wishes

From Lisa Xmas 1960

[vii] This was before the Road Safety Act of 1967 introduced a legally enforceable maximum blood alcohol level for drivers in the UK.

“Showing off”

7. These visits were probably occasions of people laughing at my antics, and my repeating them therefore, till I was scolded (“Stop showing off!”) by my Dad — which is painful to think about even to this day. I remember quipping, “What kind of a joint is this?” on one occasion — I can’t remember exactly where. This triggered a reaction of hearty laughter; so, at what I considered an appropriate juncture, I repeated it: “What kind of a joint is this?” More laughter ensued. But a third “What kind of a joint is this?” brought a stark, stinging rebuke that sent me into shamed silence.

Russell and Molly Latham

8. The names Russell and Molly Latham come to mind; were they also “Uncle” and “Auntie”, and part of the “gang”? I don’t remember visits to them; I remember them in the context of transportation, but not the motorbike and sidecar. For they had a Devon

Caravette, a Volkswagen minibus converted to have an interior like a

caravan;[viii] and I remember this because of one or two trips in it, perhaps

ca.1960, along with Mum and Dad and our Steven. We went through the Lake District on one such trip. I remember sitting in the middle of the front bench-seat next to Russell; and when night fell, I “helped” him in his driving by pressing the foot-operated switch to dip the headlights whenever another vehicle came into view.

- [viii] The Devon Caravette was first produced in 1957.

“Nitrone tracks”

9. It was around this time that the 15–chapter movie serial Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars, made in 1938, was shown on TV, in which hurricanes and other meteorological disasters were striking Earth. These were being caused by a “Nitron Lamp” on Mars, operated by Azura queen of Mars and Ming the Merciless formerly emperor of the planet Mongo. It was draining the Earth's atmosphere, or the “nitron” from the atmosphere, as part of a plan to conquer Earth. Flash Gordon and his associates travelled to Mars in a rocket ship to put a stop to it. Watching the TV show, I heard the word nitron as “nitrone”. In my imagination it started to present a threat again; perhaps someone else — the Jake

Lads?[ix] — had learned the technique and were applying it. Cars were being blown off roads; so the solution of

Rainmac-Crocodiles[x] was to equip roads with multitudes of tramway-like tracks — “Nitrone tracks” — for cars and other vehicles to go along. On a rainy day, looking out from the sidecar, I could make them out on the road surface as the vehicles passed.

- [ix] Jake Lads — introduced in Class 4, par.9: “Rainmac and the Jake Lads”

[x] loc. cit.

Less local trips

“Brock”

10. As regards day trips farther afield by motorbike and sidecar, one favourite location was “Brock”, about 19 miles away to the east in the foothills of the Pennines. This was a grassy, wooded area by a stony little river, just before a bridge over the river. The approach was along narrow country lanes, with a very steep gradient down just before we got there. I think the road sign at that time said it was “1 in

4”.[xi] Indeed, I seem to think that we would have to walk back up that hill, while my Dad drove the motorbike and sidecar, because it wasn’t powerful enough to make it up there with us all aboard. There was a more roundabout route that we took on one occasion (or more than one), by crossing the river, going up a more moderate gradient, and crossing back over the river farther downstream.

[xi] I notice in 2018 in Google Street View that the gradient is given on the modern road sign as the ratio “1:5”.

“Brock”, from Higher Brock Bridge, as seen in Google Street View, image capture Apr. 2010 © 2018 Google

Image courtesy of Ordnance Survey © 2018 Microsoft

The approach was north-east along the road coloured dark yellow, turning right into Brock Mill Lane. The “very steep gradient” is marked with a double chevron. The area where we’d park and stroll is just to the right of the double chevron. Nowadays, Ordnance Survey indicates it as a “parking”, “picnic” and “walks or trails” site.

Google Maps calls it “Brock Bottoms Picnic Site”, although according to Ordnance Survey “Brock Bottom” is almost a kilometre downstream. The “more roundabout route” would involve continuing across Higher Brock Bridge, going along White Lee Lane, then turning right and re-crossing the river at Walmsley Bridge. The river is marked on the Ordnance Survey map as “River Brock”, though at this point

Google Maps knows it as “Winsnape Brook”. The Brock is a left tributary of the River Wyre, their confluence being just east of St. Michael’s on Wyre.

The route to Brock (image courtesy of Ordnance Survey © 2018 Microsoft).

Click on the map for a larger view.

At the start of the route, the plotted line shows it as along the “B5412”. At the time, though, this was the main A585; the road shown in green and marked “A585” would not be constructed till 1967; cf.

Monday 24th July

1967.

“So very familiar… somewhat less familiar”

11. It was perhaps going to “Brock” that initially acquainted me with the first part of that route (subsequently seeming so very familiar, for it was used for several other destinations as well): along the long, quite straight A586, passing the sign

“GREAT ECCLESTON”, but not actually going through that village; passing on our left a bend in the River Wyre, surprisingly looking a lot narrower there than did the more estuarial part of the Wyre as seen from Stanah or Skippool Creek (journeys of

ca.2 and 2½ miles, respectively, also facilitated by the use of the motorbike and sidecar); passing the sign

“A586 ST MICHAELS ON

WYRE”, which was followed by a sight of the squat, square, stone tower of the late mediaeval church of St. Michael, and a fairly sharp left turn before we got to that to cross the River Wyre by a narrow, humped stone bridge, a bridge so narrow that with the advent of motorised transport a girder pedestrian bridge with tubular steel handrails was provided to the right of it.

“A sight of the squat, square, stone tower of the late mediaeval church of St. Michael, and a fairly sharp left turn before we got to that”, as seen in

Google Street View, image capture Aug. 2015 © 2018 Google

Before the end of that road, we passed through a wooded area and a sign “Churchtown”, with a few buildings to the right — but no church — in evidence.

Somewhat less familiar-seeming, though no less frequently travelled, was the main A6 road, called here Preston Lancaster New Road, into which we turned right. Nor do I have a clear memory of the narrow country lanes into which we made a left turn farther along, and proceeded to “Brock”.

“Nicky Nook”

12. Less frequently visited, and therefore with almost no mental picture now, but nevertheless favoured as a destination, was “Nicky Nook”, some four miles northwest or north-northwest of “Brock”. This was approached by even narrower country lanes, and I seem to remember a shallow ford there or on the way

there.[xii] Apart from that, all I can picture is a stream in a wooded

valley.[xiii] I have memories of bluebells, if we went in May, around the time of my birthday, either here or at “Brock”.

The positions of “Brock” and Nicky Nook (image courtesy of Ordnance Survey © 2018 Microsoft).

Grize Dale, Grizedale Brook and Nicky Nook (image courtesy of Ordnance Survey © 2018 Microsoft)

- [xii] Tracing the route in Google Street View failed to find a ford, though I suppose that in the intervening years it could have been replaced by a simple, low-lying beam bridge.

[xiii] I was surprised to discover, when I was writing this account in 2018, that Nicky Nook is in fact the name of the hill to the north of Grize Dale, and what I thought of as “Nicky Nook” is the wooded valley of Grizedale Brook. So we never got to or climbed Nicky Nook itself.

Other destinations

13. Other places we paid a visit to or passed through by the motorbike and sidecar come to mind:

- the White Scar Cave, a natural cave beyond Ingleton and in front of Ingleborough (the second highest mountain in the Yorkshire Dales) to its west, into which an access tunnel has been cut to facilitate public access (I remember being scared to enter it, lest it collapse and trap me inside, till my Mum pointed out how long it had been in existence without there ever being any such mishap);

- Kirkby Lonsdale, a small town, through which we passed on a few occasions, which has stuck in my memory because everyone said “Kirby” /ˈkəːbɪ/ but the road sign on entering it spelled it “K‑i‑r‑k‑b‑y”

/ˈkəːkbɪ/;

- Lancaster: trips there could either be undertaken via the “very familiar” route, followed by the “less familiar” A6 road

(cf. par.11) northwards, or by turning left near the start of the “very familiar” route, and crossing Shard Bridge, a toll-bridge over the River Wyre; there used to be warnings on that road that it was liable to flooding at high tide;

Imagery © TerraMetrica, map data © 2018 Google. In this context, “226 Fleetwood Road South” is anachronistic; at the time the address was “Overdale, Fleetwood Road”. The presence of the M6 motorway on this map, and of all the motorways on the other maps, is likewise anachronistic.

I have plotted the places I mentioned, above, all on one map; I don’t mean to imply that I remember our actually taking this route, though it’s possible.

Location of White Scar Cave (image courtesy of Ordnance Survey © 2018 Microsoft)

- other locations north of the River Wyre, accessed by Shard Bridge:

Knott End (shown on the map below — also visited by passenger ferry from Fleetwood);

Glasson Dock at the mouth of the River Lune;[xiv]

Shard Bridge, seen from its northern end, before the structure was demolished and a new one constructed in 1993 a little farther downstream (to the right from the viewpoint of this photo) (© Blackpool Gazette)

- [xiv] I subsequently visited Glasson Dock on Monday 30 August 1971 with friends — “We all went from Garstang to Glasson Dock, an interesting place visually, with boats in the dock, and lock gates, approached by the road that leads over the flat tidally-flooded land. The sun as setting cast a very yellow hue indeed over everything” — and on

Friday 9 July 2004 with my Mum and Dad (q.v. for photos of the place).

- the Trough of Bowland, a valley and high pass in the picturesque Forest of Bowland (very little actual

forest there!);

Imagery © TerraMetrica, map data © 2018 Google — apart from “Trough of Bowland” which is mine

I’ve plotted a route that outward takes us along the “very familiar” route, followed by the “less familiar” A6 road as if going to “Brock”. Because the Trough of Bowland is a location one would go through not go to, I have made it a circular trip, returning via Shard Bridge. I have thrown in a diversion to Glasson Dock, for good measure!

Location of the Trough of Bowland (image courtesy of Ordnance Survey © 2018 Microsoft)

- Blackpool Illuminations, the annual six-mile-long light show along the Promenade, run every year from late August until early November: we would join the queue of very slow-moving cars at Starr Gate at the south end and leave it at Bispham in the north, initially passing under the “festoons of garland lamps” with thousands and thousands of light bulbs, then after North Shore passing scores of different-themed animated tableaux on the cliff tops, behind the tram tracks which were to our left; on these occasions, I would occupy the front seat of the sidecar and my Mum would squeeze herself into the back, and the soft cover of a rectangular part of the roof would be removed for me to poke my head out for a better view — though on one occasion, we made the journey by tram, which was unsatisfactory because of restricted visibility and the speed at which the tramcar proceeded;

- Morecambe Illuminations: we went to see this light show one year; but compared with Blackpool’s illuminations, this so-called “spectacular wonderland of light” was a big disappointment — held, as it was, to walk through, in the seaside

resort’s[xv] main park (Happy Mount Park), not to motor through, along mile after mile of promenade, as was Blackpool’s.

[xv] For the location of Morecambe, see the map under the item “Lancaster”, above.

“…The first motorbike and sidecar; … the second one”

14. Having touched upon both local journeys and longer day trips by the motorbike and sidecar, all from home and returning home, before I go on to recall holidays away from home, I want to expand upon my Mum’s earlier statement: “It was in 1959 that Dad got the first motorbike and sidecar; and it was only a few months afterwards that he got the second one with the Busmar sidecar.”

“AYO 451”

15. The first sidecar had a hinged top that opened towards the machine, and a half-door in the side to give access. The top was fastened from the outside, so the occupants couldn’t get out till the driver released the clips. There was room in the sidecar for one adult and one child. (I was nine in May of that year.) The number on the front and rear registration plates was “AYO 451”. I’m not sure whether both motorbike and sidecar were manufactured by BSA (The Birmingham Small Arms Company).

A similar motorcycle and sidecar to our first one

Where, I wonder, did we put the luggage when we went on holiday to Auntie Monica and Uncle Clifford’s in Sheffield?

My Dad’s accident

16. My Dad had an accident, and when he came home he had cuts and bruises, in particular a deep-gouged wound in his leg that persisted seemingly for ages. He had taken out just the bicycle and the chassis-and-third-wheel with no sidecar mounted on it, and it had overturned when he was making the left turn from Fleetwood Road into Anchorsholme

Lane.[xvi] I’m not sure in connection with which vehicle it was, that the accident occurred.

- [xvi] In those days, Anchorsholme Lane was a through road; the construction of that leg of Amounderness Way, cutting across Anchorsholme Lane, was still decades away.

“KRN 305”

17. I’m not sure whether “KRN 305”, which replaced “AYO 451”, was two-cylinder. The engine certainly had a greater cubic capacity than the other, and was more powerful; it had to be, for the

Busmar sidecar was bigger and heavier. It had a rounded front, that contrasted with the “beak-like” front of the sidecar it replaced.

“The Busmar sidecar”

The “ample luggage space” still looks hardly adequate.

An incident on the first day we had “KRN 305”

18. I remember that just after Dad brought it home, we decided that our first outing would be to Blackpool; but as we were mounting the slight rise just before the bend leftwards, where Poulton Road becomes Westcliffe Drive, the sidecar wheel bumped over a hole in the road and there was a sudden lurch leftwards, and another, and another. My Dad brought the vehicle to a halt with all haste; but, after looking around the vehicle and not finding any obvious cause, remounted and continued our way slowly and carefully. I can’t remember where our intended destination had been, but I think we then went to Uncle Jack’s. He was a coach-builder for the Blackpool coach-building business H. V. Burlingham, and his craftsmanship and mechanical aptitude were second to none. He quickly observed that the sidecar was mounted too closely over its wheel’s brake mechanism, and that the combination of the weight of the passengers depressing the sidecar’s suspension and the bump in the road had caused the sidecar suddenly to apply the brake. His temporary remedy was to disconnect the brake cable, till Dad could have opportunity to get the motorcycle dealer to reposition the sidecar.

“Where Poulton Road becomes Westcliffe Drive”, as seen in Google Street View, image capture Sep. 2018 © 2018 Google

Auntie Monica and Uncle Clifford

19. From time to time, from almost as long as I can remember, Auntie Monica and Uncle Clifford used to visit and stay at Nanny and Grandad Cooper’s house in Neville Drive, Thornton. (“Auntie” and “Uncle” were convenient familial terms to use, as with others whom I mentioned earlier; though Monica was, in fact, my Dad’s cousin.)

They came from a place called “Share Field”. When I first heard this said, the only named “field” that I was aware of was King George’s Playing Field on Victoria Road, Thornton, so I imagined “Share Field” as being somewhere beyond there. It therefore came as a shock when my Dad informed me that “Sheffield” was 90 miles away.

It intrigued me to learn that their surname was Kershaw, because that was the name of my teacher at Church Road County Primary School.

Mrs. P. R. Kershaw,

Class 5, 1956–1957

Auntie Monica worked as an assistant in the “Co-op” grocery shop near where they lived. (Because she outlived Clifford for many years, and I knew her long into adult life, there are few if any distinct childhood impressions that come to me as I think about the period under consideration here.)

“Auntie Monica”, 1974 and 1975

Uncle Clifford worked for Sheffield Corporation as a tram-driver, though perhaps by now he’d been promoted to inspector. He was a stout man whose resemblance to film director and producer Alfred Hitchcock was fairly frequently remarked upon. He wasn’t a wholly well man, and had had multiple surgeries — abdominal or thoracic, I assume, for although there was mention of much scarring, none was visible. (Latterly he had to have operations to correct ingrowing eyelashes.) He had a normal-looking left hand, and a very fat-looking right hand. He also had what looked like a raised black mole on his quite prominent lower lip. I remember that, for I also used to have a small dark mark on my lower lip.

He was the first person I knew, who had a transistor radio: a plastic, pocket-sized

Emerson radio. He also shaved with an electric razor. (My Dad and Grandad used to wet-shave with a safety razor.)

“His resemblance to

film director and

producer Alfred

Hitchcock was fairly

frequently remarked

upon.”

20. When Auntie Monica and Uncle Clifford visited, they used to like to catch the bus to Cleveleys and go to the open-air theatre, the Arena, at the far end of Victoria Road beneath the seafront promenade, for the variety shows that were staged there in summer. I think it was in that context that I first heard of versatile entertainer Roy Castle. He was said to live in Cleveleys, and I guess he must have also appeared at the Arena.

Uncle Clifford used to sing songs for Steve’s and my amusement, perhaps heard during the Arena shows:

- Tiddley Winkie Winkie Winkie Tiddley Winkie Woo

I love you.

Tiddley Winkie Winkie Winkie Tiddley Winkie Woo

I love you.

I love you in the morning,

And I love you in the night.

I love you in the evening,

When the stars are shining bright.

So Tiddley Winkie Winkie Winkie Tiddley Winkie Woo

I love you.[xvii]

And:

- I see the moon, the moon sees me,

Down through the leaves of the old oak tree.

Please let the light that shines on me

Shine on the one I love.

Over the mountain, over the sea,

Back where my heart is longing to be,

Please let the light that shines on me

Shine on the one I love.[xviii]

When we all joined in and sang this latter song, after “Over the mountain, over the sea”, Uncle Clifford added, “Pah doom, pah doom!”, which I took up.

- [xvii] Tiddley Winkie

Woo, credited to Morton Morrow, was issued as a B-side on a 78-r.p.m. record by Sammy Kaye, featuring vocalist Laura Leslie, in 1950. But before that it was variety entertainer Mavis Whyte (1922–2014) who won the hearts of wartime servicemen as the “Tiddley-Winkie Girl” with her rendition of the song.

[xviii] I See the

Moon, written by Meredith Willson, was recorded in the UK by The Stargazers, and reached number one in the UK Singles Chart in 1954.

Holidays in Sheffield

21. Every year, typically during Whit week, but sometimes in summer, we, along with Nanny and Grandad Cooper, would go on holiday, always to a coastal resort — in my memory, Bridlington, mostly; Scarborough, twice; Butlins holiday camps, on three consecutive occasions (Pwllheli, Filey, then Pwllheli again) — taken there at Nanny and Grandad’s expense, all six of us, in Mr. Armstrong’s big taxi; but now the four of us, without Nanny and Grandad, started going to stay at Auntie Monica and Uncle Clifford’s house in Sheffield. I long knew that they lived at “12 Lees Hall Road, Sheffield

8”;[xix] now I saw the house for myself, a semi-detached house built on the side of a quite steeply inclined, tree-lined road.

Auntie Monica and Uncle Clifford would vacate the upstairs front bedroom, and Mum and Dad would sleep in that. Steve and I would sleep in a room at the back. They themselves would go up more stairs to the attic to sleep. The kitchen was at the back of the house, where there was also an outside toilet. There wasn’t a toilet inside the house, and there wasn’t a bathroom either. From the kitchen, there were steps down to a cellar.

They had a huge, fat black cat called Bobby, who would sometimes sleep on Auntie Monica’s lap with on his back with his legs sticking upwards. There was a very small yellow teddy bear, and at other times Bobby would sleep cuddling this between his front paws. On a cloth tag sticking out of one of its seams there was printed or woven the single word “Foreign”; and I took this to be the teddy’s name. (It was said that when Bobby died, Foreign was heartbroken and died also; and the two of them were buried together in the back garden.)

- [xix] I long knew that they lived at “12 Lees Hall Road, Sheffield 8”: Obviously, I didn’t know that while I still thought they lived in “Share Field”.

Routes to Sheffield: “Snake Pass” and “Woodhead Pass”

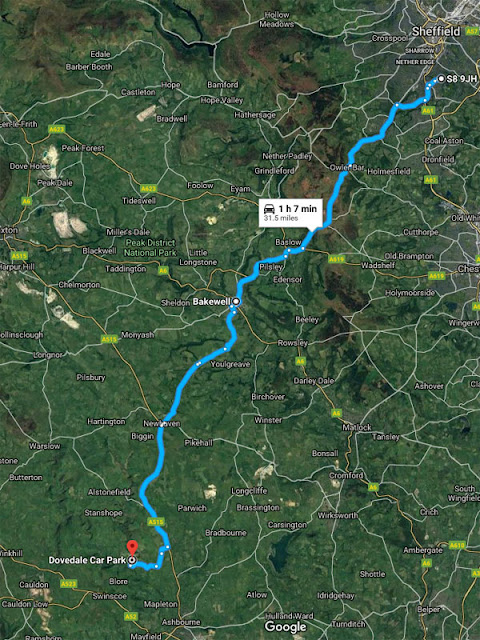

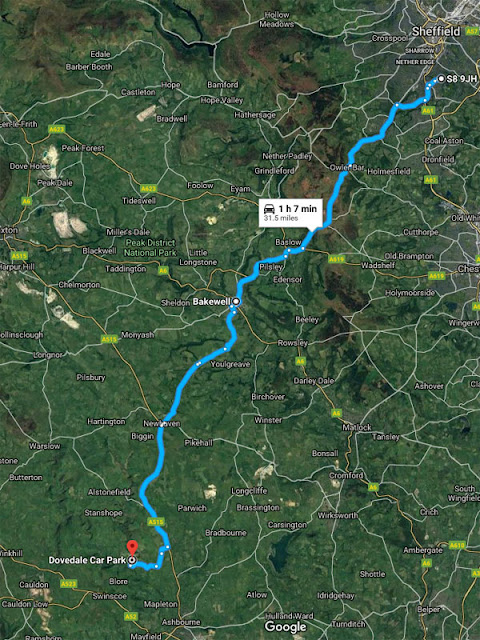

22. How did we get to Sheffield? To travel from Lancashire, where we lived, to Sheffield, in south

Yorkshire,[xx] one had to cross the range of mountains and hills that formed a barrier, north to south, between the two, the Pennine Chain. The two roads through the Pennines, from Manchester to Sheffield, that my Dad mentioned as our options, were: the Snake Pass, which at 40 miles was the shorter, but it had roads without fences winding around the hillsides, with a sheer drop to one side; and the slightly longer Woodhead Pass (almost 44 miles), which had no such hazards. The fact that I remember the name “Glossop” as that of a town we passed through, is evidence that we took the Snake route, at least once. The fact that I also remember the Ladybower Reservoir is neither here nor there, for we could have visited it from Sheffield on a day trip.

By what route we would travel the 50 miles or so from home to, or around, Manchester is gone from memory now.

Imagery © TerraMetrica, map data © 2018 Google. In this context, “S8 9JH” the postcode of 12 Lees Hall Road, Sheffield 8, in these and other maps, is anachronistic, for Sheffield did not get postcodes till

ca.1967.

- [xx] Nowadays, one would capitalise the “s” to make it “South Yorkshire”, a metropolitan county created on 1 April 1974 as a result of the Local Government Act 1972. But at the time under consideration, Sheffield was in the southern part of the county of Yorkshire, indeed of the West Riding of Yorkshire. I could be silly and say it was in the Upper Division of the Wapentake of Strafforth and Tickhill, the southernmost wapentake in the West Riding of Yorkshire.

23. Arriving in Sheffield, we approached Auntie Monica and Uncle Clifford’s house from the north. Sheffield is a hilly city; and such is the visual memory of descending southwards, with a view of the houses on the wooded valley-side of the district of Meersbrook ahead, where “12 Lees Hall Road, Sheffield 8” was, that it sometimes even appears in my dreams to this day.

Carrfield Road, Sheffield, looking southwards to Meersbrook, as seen in Google Street View, image capture Aug. 2016 © 2018 Google

At the end of Carrfield Road, we’d bear left into Albert Road, and less than 100 yards farther along where this and four other roads met, we would bear right into Upper Albert

Road.[xxi] A little over 300 yards farther along that, where Upper Albert Road bore right, we’d carry on more or less straight ahead into Lees Hall Road.

Lees Hall Road, Sheffield, looking uphill southwards, as seen in Google Street View, image capture Jul. 2016 © 2018 Google

- [xxi] We would bear right into Upper Albert Road — i.e. the opposite end of Upper Albert Road from that mentioned in

par.25, below.

Routes to Sheffield: “Over Mam Tor”

24. I think, after we had started to visit the caves in the vicinity of Castleton, that we travelled from Manchester to Sheffield “over Mam Tor”. It is not strictly correct to say, “Over Mam Tor”, because Mam Tor is the name of a hill and we didn’t go “over” it; so we should have said “passing Mam Tor”, or “through the Hope Valley”. My memory of the name of a small town we passed through — Chapel-en-le-Frith — may come from this

journey, as also may the abiding memory of the nearly 600-yard-long, 22-arch, brick-built railway viaduct towering 37 yards above the valley of the River Mersey, which always, to my mind, characterises Stockport.

Imagery © TerraMetrica, map data © 2018 Google

Edgeley Viaduct, Stockport

Image capture Jul. 2018 © 2019 Google

At the time, our route would have been the one shown in this image from Google 3D view, passing by the foot of Mam Tor. But the continual landslips, caused by unstable lower layers of shale, which give Mam Tor its alternative name of The Shivering Mountain, resulted in repeated repairs to this part of the road being abandoned in 1979.

Imagery © 2018 Google, Landsat / Copernicus, Data SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, Map data © 2018 Google

Our route would have been along what is here shown as an unfenced road to the east of Mam Tor, with a hairpin bend at its north end, then passing Treak Cliff Cavern as the road descended to Castleton.

Image courtesy of Ordnance Survey © 2018 Microsoft

25. The approach to Lees Hall Road from the south-west, after going along the Hope Valley route, seems more familiar to me than the northern approach, after following the Snake or Woodhead routes (even if I have seen this, or some distorted version of it, in my dreams on more than one occasion!). Perhaps, though, that familiarity stems from returning from the south-west on several occasions from outings. Many of the roads in Sheffield, we observed, confusingly had the same name, distinguished from each other only by being called additionally “Lane”, “Road”, “Avenue”, “Rise”, or “Crescent”. So it was that at a fork at its end, Norton Lees

Lane was joined from the left by Norton Lees Road. The continuation beyond the fork was Lees Hall Avenue (“Avenue”, please note: not “Road”).

Just to the left there, was an old timber-framed house (“The oldest building in Sheffield,” Uncle Clifford told us); and a little over 250 yards farther along, where one might expect the more direct, somewhat downhill way ahead still to be called Lees Hall Avenue, and the way bearing right from there going uphill to be called something else, the reverse was true: the way ahead was Upper Albert

Road;[xxii] and to the right, it was still Lees Hall Avenue. We would take the latter way. Some 230 yards farther along, it was crossed by Lees Hall Road; and we would turn left, going down to Auntie Monica and Uncle Clifford’s house on the left side.

- [xxii] The way ahead was Upper Albert Road — i.e. the opposite end of Upper Albert Road from that mentioned in one of the image-captions

above (par.23).

Bishops’ House, “the oldest building in Sheffield,” as seen in

Google Street View, image capture Aug. 2016 © 2019 Google

(Ahead, left:) Upper Albert Road, (ahead, right:) Lees Hall Avenue, as seen in

Google Street View, image capture Sep. 2015 © 2018 Google

Lees Hall Avenue, as seen in Google Street View, image capture Aug. 2016 © 2018 Google. The far shop is still a “Co-op”; cf.

par.19.

Lees Hall Avenue, approaching where Lees Hall Road crosses it, as seen in Google Street View, image capture Aug. 2016 © 2018 Google

Lees Hall Road, Sheffield, looking downhill northwards, as seen in Google Street View, image capture Aug. 2018 © 2018 Google

12 Lees Hall Road on the left is much altered from when we used to visit it. The extension with a dormer window, beyond it, wasn’t there in our time, and the ground in front of it hadn’t been excavated, so there were a couple of steep steeps up.

12 Lees Hall Road — Google Street View screen-captures that I made, April 2010 © 2010 Google

Day trips

26. From there we would go on day trips, especially to the Peak District of Derbyshire and the Derbyshire Dales.

I remember that the first motorbike and sidecar used to struggle with some of the steep gradients. Normally the sounds of each combustion in the cylinder would follow each other so quickly as to create a whirring sound; but when going up steep hills, they slowed to

a-pak-a-pak-a-pak-a-pak-a-pak-a-pak-a-pak a-pak-a… And I remember that we had to stop on more than one occasion when the engine got overheated, to give it time to cool down, before we resumed our journey. We may have had to do the latter also with the motorbike that replaced the first one; they had air-cooled engines, and there wasn’t much air passing through the cooling fins of the cylinder during a snail’s-pace crawl up a hill.

Castleton: Blue John, Treak Cliff, and Speedwell Caverns

27. I have already mentioned the caves in the vicinity of Castleton. On each trip there we visited a different one. There are four caves in all, accessible to the public for guided visits, but we only visited three of them; this means that we visited Castleton three times — perhaps three years in succession. I can remember the order in which we visited them: Blue John Cavern one year, Treak Cliff Cavern another, and Speedwell the last.

The first two caverns were discovered while mining for Blue John, a semi-precious mineral with wavy purple-blue and yellowish bands. In fact, Blue John is still excavated in parts of these, and the miners serve also as guides for the underground public tours. As well as mine workings, we also saw natural rock formations of flowstones, stalagmites and stalactites. I was much more impressed with Treak Cliff Cavern, because it had more of these than did Blue John Cavern.

I don’t think I had the qualms about entering, that I’d had with the White Scar Cave

(par.13), and about descending the many steps in them; so my Mum’s words of reassurance must have been convincing. On one of the visits, I remember that it felt quite cool there in the underground depths — it was a hot, sunny day outside — but the guide said that it was the same, constant temperature throughout the year, so if we’d come in winter it would have felt warm.

I think it was at Treak Cliff Cavern, at the visitor centre as we waited for the previous party to emerge and the turn of the next party to descend, that something happened to make our Steve and me chuckle with amusement. There were two girls in their early teens, and one said to the other, “Shall we eat the apples that Mummy gave us?” The other replied, “Oh,

do let’s!” So afterwards, Steve and I kept saying to each other, “Oh,

do let’s! Oh, do let’s!”

Speedwell Cavern was originally a lead mine. After descending many steps, we got into a boat; the guide lay on his back and legged the boat through a long, low horizontal tunnel, till it came to a large cave where we got out to see the natural rock formations and the high and deep shaft called the “Bottomless Pit”.

The show cave that we didn’t visit was Peak Cavern; the closest we got to that was seeing the entrance: a gaping mouth in the cliff at the head of a gorge, out of which a stream flowed, and above which was the ruin of Peveril Castle.

The entrances to Treak Cliff and Blue John Caverns were accessed from the main

road,[xxiii] the former on the left about a mile out from Castleton, after the road turned from a westerly to a more northerly direction. A little over half a mile beyond there, there was a hairpin bend and the road wound southwards, with the landslip-prone hollow face of Mam Tor, the “Shivering Mountain” to its right. Just beyond Mam Tor, on the left, was the entrance to Blue John Cavern. Speedwell Cavern, about ¾-mile from Castleton, was accessed from a road that forked left of the main road about ¹⁄₃-mile out from Castleton. Beyond Speedwell was Winnats Pass, a more direct way through than the hairpin main road, but not used on our travels because it was so steep. We did visit it at least once, though, as the photo below shows. We may have got to it from the west after going around by the hairpin road, because in that direction the steep incline was downwards.

Steve, Mum, me, and part of my Dad’s thumb, on Winnats Pass near Castleton, Derbyshire. I am wearing my Church Road County Primary School tie.

- [xxiii] The main road: This is written from the standpoint of then, for it was abandoned as a through road in 1979 because of repeated landslips from Mam Tor.

Buxton and Bakewell

28. I remember the fact that we visited spa town and market town Buxton, probably more than once, but have no specific memories that I can relate. We probably visited the Pavilion Gardens; and given our liking for show caves, engendered by visiting the ones near Castleton, we may have gone to the extensive, multi-chambered Poole’s Cavern on the outskirts of the town. A memory of a guide turning out his light and plunging us into complete darkness for several seconds may come from here (if not here, then somewhere!).

Clearer in my memory is Bakewell on the way to Buxton, and in particular the bridge there over the River Wye. For I had a couple of little

I-Spy books, spotters’ guides for children; in them were listed items to look out for, and a number of points, varying according to how unusual the sightings were, would be awarded for spotting them. One of the books was №31 in the series, “Bridges”; and the 13th century five-arched stone bridge, and in particular the triangular shape of the bulwarks of its piers, was one of the things that earned me points. I can’t remember what the other

I-Spy title was: №10, “On the Road”?

Imagery © TerraMetrica, map data © 2018 Google

Stately homes

29. One year we visited the large stately home Chatsworth House, the seat of the Duke of Devonshire, originally dating from the 16th century, but with much 17th and 18th century addition and rebuilding, set in 105 acres of parkland on the east side of the River Derwent. The following year — passing through Bakewell, as we had done going to Buxton — we visited the mediaeval and Tudor country house Haddon Hall by the River Wye, one of the seats of the Duke of Rutland. I liked this better, because it seemed altogether more homely and habitable, and less museum- or art gallery-like, than Chatsworth.

Imagery © TerraMetrica, map data © 2018 Google

Dovedale

30. Another destination, reached by going through Bakewell, was Dovedale. I remember crossing by the stepping stones, but how far along the steep-sided wooded valley we went I don’t remember. I remember passing a large limestone natural arch on the way. (When I went camping with Church Road County Primary School near Ashbourne, Derbyshire, perhaps in the Easter holidays 1961, I remember getting all excited when we visited and walked through Dovedale, because I’d been there. “Just along here, you’ll see a natural

arch…”)[xxiv]

- [xxiv] Swimming lessons at Beechwood School records another instance of my getting all excited when I and my classmates were doing something that I’d already done.

Imagery © TerraMetrica, map data © 2019 Google

Tideswell, Eyam, Monsal Dale

31. I don’t know why “Tideswell” seems a familiar name, but we were presumably there at some point. “Monsal

Dale”[xxv] is another familiar name, so we must have visited that and seen the 300-foot-long railway viaduct, Headstone Viaduct, with its five 50-foot-span arches, rising at its centre some 70 feet from the valley floor. The village of Eyam is on the way to both these places, and I do remember that we stopped there once. We presumably visited the museum, and learned that during the Great Plague of London in 1665, some flea-infested cloth was received from London by the local tailor and people started dying. The decision was taken to quarantine the entire village to prevent the disease from spreading farther afield. The plague left 83 survivors out of a population of 350.

-

[xxv] in a letter from my Mum dated 19 May 1994, she replies to an objection I raised to a previous statement that she’d made, and writes: “You are right when you say you were older than 5 or 6 when we went to Monsal Dale — we didn’t get our first motor bike until you were nine.”

Imagery © TerraMetrica, map data © 2019 Google

Destinations to the south of Sheffield

Imagery © TerraMetrica, map data © 2018 Google

32. Going south from our location in “Sheffield 8”, the first large town we’d come to, a little under 10½ miles away, would be Chesterfield, with its landmark Church of St. Mary and All Saints with the “crooked spire” — crooked in two ways: inclined and twisted. The timber-framed octagonal spire, clad in lead plates in herringbone pattern, leans about 9½ feet to the south-west, and has a spiral twist of about 45° anticlockwise as viewed from above.

Imagery © 2019 Google, map data © 2019 Google

Nearly 23 miles from “home” were Matlock and Matlock Bath. We went here on at least one occasion. Matlock Bath, especially, lies within a winding gorge of the River Derwent. We probably ascended the Heights of Abraham there by a steep zig-zag footpath to admire the views of the valley from the top and see the Victoria Prospect Tower there. I don’t recall whether we visited the show caves there.

Once, we went beyond Matlock Bath to the Tramway Museum at Crich,[xxvi] 28 miles from “home”. This was opened at a time when most towns were getting rid of trams, though Blackpool and Sheffield still had

them.[xxvii] Nevertheless, I think there were examples from both Blackpool and Sheffield at the museum, as well as ones from cities that no longer had trams.

- [xxvi] Our visit was when the museum was in only the early stages of its development; there were only static displays, with no actual trams running. “After a sustained search across the country, in 1959 the [Tramway Museum Society]’s attention was drawn to the then derelict limestone quarry at Crich in Derbyshire, from which members of the Talyllyn Railway Preservation Society were recovering track from Stephenson’s mineral railway for their pioneering preservation project in Wales. After a tour of the quarry, members of the society agreed to lease — and later purchase — part of the site and buildings. Over the years, by the efforts of the society members, a representative collection of tramcars was brought together and restored, tramway equipment was acquired, a working tramway was constructed and depots and workshops were built. Recognising that tramcars did not operate in limestone quarries, the society agreed in 1967 to create around the tramway the kind of streetscape through which the trams had run and thus the concept of the Crich Tramway Village was born”

(Wikipedia).

[xxvii] Sheffield trams stopped running in October 1960.

Well dressing

33. I have a vague memory of occasionally passing through a village, and seeing an intricate picture made of flowers around the well in the village square. My Mum told me that it was called “well dressing”, and that it was a custom in Derbyshire.

Nottingham Castle and the Major Oak

Imagery © TerraMetrica, map data © 2018 Google — apart from “Nottingham Castle” and “Major Oak”, which are my additions

34. We didn’t always confine ourselves to destinations in Derbyshire; one day we went to Nottingham and visited the Castle. The crooked spire of Chesterfield would have come to our attention on the way.

The Adventures of Robin Hood was a television series comprising 143 half-hour, black and white episodes broadcast weekly in the late 1950s on ITV. It starred Richard Greene as the outlaw Robin Hood who lived in hiding in Sherwood Forest, and Alan Wheatley as his nemesis, the Sheriff of Nottingham. Sometimes the scene of swordplay and derring-do was Nottingham Castle, portrayed as a fortified place with crenellated towers and curtain walls, moat and drawbridge, gateway and portcullis.

Chris

Woodhead, who at that time lived in Grimsby and whom I wouldn’t meet for another few years, wrote in 2018:

- I was a fan of Richard Greene as Robin Hood. I remember that during that time, [Auntie] Joan and [Uncle] Gordon took [my cousin] Brian and me on an outing to Nottingham. Gordon didn’t have his own car at that time, and we made the journey in

E. A. Hall’s van! Because of my fascination with Robin Hood, I was quite excited about going on this trip (thinking that we would also see Sherwood Forest). I felt somewhat cheated, however, on seeing Nottingham Castle. It was nothing like the way it was portrayed in the TV series, and more like a boring stately home stuck on the top of a hill! … On our return journey to Grimsby, … Gordon took a minor road out of Nottingham and, once out in the countryside, pulled up at the side of the road near what could only be described as a copse or, at the most, a small wood. There, he tried to convince Brian and me that this was indeed Sherwood Forest! We wanted to believe him but were sceptical. Then, as I remember, Joan intervened and said, “You boys don’t really believe that Robin Hood and all his men could have hidden here from the Sheriff of Nottingham for long, do you?”. Well— no we didn’t.

I remember having exactly the same impression of Nottingham Castle, when we visited it: nothing like a “castle”. I should have been prepared for this, really; for both my parents smoked, and I would have seen numerous times the trademark image of Nottingham Castle on the back of

Player’s cigarette packets.

From there we went on to see the Major Oak in Sherwood Forest (where Robin Hood and his merry men had supposedly slept), all propped up with poles. Its sparsely treed environs were disappointingly not very forest-like. I remember on one occasion going through Worksop and thinking that the name was like “workshop”, so that may have been the way we returned to Sheffield.

Visits to relatives

35. My Dad came originally from Sheffield, so there was inevitably the visiting of relatives to be undertaken. The only visits that I remember are these:

Uncle Joe and Cousin Joyce

36. Dad’s Uncle Joe was Grandad Cooper’s older brother; and he looked like him, I thought, when I met him for the first time. He lived in Greystones, a neighbourhood of Ecclesall — to the west of Meersbrook, Sheffield, where the Kershaws

lived.[xxviii] He was a widower, and he lived with his unmarried daughter Joyce who was a school-teacher.[xxix] It was a mistake to ask Uncle Joe how he was. “Oh,” he would reply, “I’ve been bad lately!” He had been an engraver in the cutlery-manufacturing industry, and he demonstrated his art admirably in the pencil designs that he drew in Steve’s and my “autograph”

books.[xxx]

J. Fox Cooper

July 30/1960

with LOVE

to

JOHN

This is the only documentary evidence I have of the date of our visits to Sheffield.

- [xxviii] The fact that Auntie Monica worked for the “Sheffield and Ecclesall Co-operative Society Limited” suggests that the two were considered as separate towns, almost.

[xxix] This is the family lore concerning Joyce:

-

- She was just nine months younger than my Dad. Apparently, Uncle Joe and his wife came to see him when he was born; and they went home that night, and she must have conceived because Joyce was born just nine months after. They were so taken that they decided they’d try for a family themselves. Uncle Joe had been married before; but she had died in an abortive child-birth, and he didn’t want to risk his second wife dying. Seeing my Dad, however, they decided that they would risk it. So Joyce was born just nine months after he was. Joyce was very bright — she was a school-teacher — and she was very musical; she used to conduct when they had the massed choirs in the park at Whitsuntide. That was when all the Sunday Schools used to mass in Norfolk Park, in Sheffield; they’d have a big orchestra there; and Joyce would conduct the lot.

- [xxx] See also My poetry manuscript book: Saturday 30th July

1960, and see the start of that story for the origin of the “autograph” books.

Sasha

37. On one visit, Joyce had a friend staying with her called Sasha. I can’t remember what her story was, but I know I was intrigued by her. She may have been from eastern Europe, a refugee from behind the “Iron Curtain”, perhaps. At that time nearly every grown-up smoked, but Sasha was expressing a desire to give up cigarettes. There ensued a buzz of conversation, and she didn’t hear my suggestion “Try chewing

gum.”[xxxi] But at a lull, I suggested in full, “If you want to give up smoking, why don’t you try chewing gum?” — to which she replied, “It dazz not verrk!”

- [xxxi] Chewing gum — i.e. “chewing” (gerund) and “gum” (noun), not the compound noun “chewing-gum”, and the same in the following sentence.

Auntie Gertie

38. Once, we met Auntie Gertie. She was the older sister of Grandad Cooper and Uncle

Joe.[xxxii] She looked like a skinny version of my Grandad in a frock wearing a white wig! I’m not sure where this was, but rightly or wrongly the memory of her is associated in my mind with a visit to a pub in

Hathersage.[xxxiii] Because children weren’t allowed in the bar, Steven and I amused ourselves in a room in the adjoining living quarters.

- [xxxii] Herbert Cooper, my Grandad, was the youngest, born in 1887, Joseph Fox Cooper was three years older than Herbert, and Gertrude three years older than Joseph. So they were aged

ca.73, ca.76 and ca.79, respectively, at this time. There were three other siblings, whom I never met: George Arthur, three years older than Gertie; and Millicent Annie and Alfred Ernest, whose ages I don’t know.

[xxxiii] For the location of Hathersage, see the route “over Mam Tor” plotted in

par.24. I have no information about who owned or ran the pub. There is no account of any such ownership on my Dad’s father’s side, though there is on his mother’s side — but that wouldn’t shed light on why

my Dad’s aunt and the pub occur together in my memory.

“Grandad Cooper”

The Little John Hotel, Station Road, and George Hotel, Main Road, Hathersage — possible candidates?

Image capture Aug. 2016 © 2019 Google

Miscellaneous other memories from visits to Sheffield

A tram ride

39. I think we had a ride on a Sheffield tram.[xxxiv] Whether we got on for free because Uncle Clifford worked on the tramways, I don’t remember. We didn’t ride on any of the buses, but I remember thinking they looked like the new Blackpool buses; they were the same cream colour, though with royal blue trim as opposed to Blackpool’s green. They were also half-cab, as opposed to Blackpool’s full-fronted.

- [xxxiv] Sheffield trams stopped running in October 1960. Although tramways have been revived in a number of cities, including Sheffield, the last surviving first-generation tramway is Blackpool’s.

Parks and woodlands

39A. Before we got the motorbike and sidecar and I saw Sheffield for myself, there had been two things about the place that had been repeatedly stated by those who came from there (Nanny Cooper is the one who mainly comes to mind as I think about this): first, that it was very hilly — the assertion, that it was built on seven hills, as Rome was, may also have been made — and second, that although it was a “city” and you might therefore expect it to be all built up, there was nevertheless a lot of green and there were many parks there.

Indeed, when we got to Sheffield, “12 Lees Hall Road” proved to be built on quite a steep hillside on a tree-lined road. If one walked uphill from there, turned left, and walked 300 yards or so to the end of Lees Hall Avenue, as Steven and I did on one or two occasions, there was the quite extensive Carr Wood at its end, through which the Meers Brook wound. From the edge of that wood there was a view north down to the River Don valley and a panorama of the hilly cityscape beyond.

Graves Park, at 230 acres, is, I think, the largest park in Sheffield. We may have visited it; we certainly passed by it, on the way to places such as Chesterfield. But it wasn’t a “park”, as I thought of parks at that age, that is one having children’s play areas. The park like that, which I remember, was Millhouses Park, about a mile more or less west of Graves Park, in the south-west part of Sheffield. It was long and narrow — about three quarters of a mile long in a northeast–southwest direction; about 85 yards wide at its narrowest, and about 140 yards at its widest — squeezed as it was between Abbeydale Road South (the main road to Bakewell) on the north-west side, and the railway line that went on through the Hope Valley on the south-east side. Through its whole length, alongside the railway, flowed the River Sheaf. This is only a stream, really, and in part of the park, its course had been restructured to form concrete pools where model boats could be sailed. I had a 14"-long, battery-powered, plastic model boat, a brown and white Tri-ang

“Derwent cabin cruiser”, which I sailed there. The roof was detachable to give access to the batteries. It had no remote control; you just switched it on, set the rudder, placed it in the water, and walked to where you hoped it would come to “shore”. (I think our Steve had one, too.)

The Derwent cabin cruiser

I can’t remember what became of it; but cf. Two inches away from being blinded,

par.1.

“Journey to the Center of the Earth”

40. On one occasion, we looked through the cinema listings in the local newspaper — the

Star or the Sheffield Telegraph — and decided on the sci-fi adventure film

Journey to the Center of the Earth,[xxxv] being shown in a cinema in a village not far from Sheffield. We went there by motorbike and sidecar on this, the first of several times that I saw it. (Indeed, during the aforementioned camping holiday with the school to near Ashbourne, perhaps around Easter 1961, I remember describing the plot of the film to those with me — boys and perhaps a teacher — in intricate scene-by-scene detail, in the big bell-tent where we slept.)

- [xxxv] This film was released in December 1959, so if this is indeed the one that we saw, it would have been during our summer 1960 visit. There was a number of sci-fi/fantasy films produced around this time.

Fitzalan Square[xxxvi]

41. We saw the 1956 French fantasy comedy-drama short film The Red Balloon actually

in Sheffield, at the Cartoon Cinema[xxxvii] on Fitzalan Square. (It must have been part of a double feature, because it was only 34 minutes long.) There were scenes in the film where there were flights of steps from one level of the city to another, and indeed there were steps from Fitzalan Square that reminded me slightly of them.

Flights of steps at the south-east corner of Fitzalan Square

Imagery © 2019 Google, map data © 2019 Google

Looking up to Fitzalan Square from Bakers Hill

Image capture Nov. 2015 © 2019 Google

I found some of the dull and slummy Parisian cityscapes depressing, and the sight of the balloon, shot by a bully’s catapult, wrinkling and deflating, near the end of the film, disturbing.

At the time, somewhere in the square, I remember seeing a poster or hoarding advertising the film

Exodus, and I remember thinking that it might be a biblical epic like the 1956 film

The Ten Commandments, or the 1959 film Ben Hur,[xxxviii] which I’d seen perhaps the previous year, with lots of spectacular special effects that would make it exciting to

see.[xxxix]

Perhaps in connection with a bomb that fell on a building on Fitzalan Square during World War II, killing 70 people, I remember hearing stories and perhaps seeing old newspaper clippings of the “Sheffield Blitz”, when German

Luftwaffe bombing killed hundreds of people and caused tens of thousands more to be made homeless in the devastation. Sheffield had much heavy industry, in particular steelworks and in the war armaments manufacture, and the Germans were primarily targeting these.

The only other abiding memory of Fitzalan Square is of the public toilets, the ones signed

“GENTLEMEN”, anyway: they were underground; and the feature about them, that I hadn’t encountered anywhere else before, was that there were a separate entrance with steps down and exit with steps up, at opposite

ends.[xl]

- [xxxvi] Not part of my memories, and therefore footnoted, is the following family-lore concerning uncles on my Dad’s mother’s side; he told me:

-

- My Uncle Charlie had the Bell Hotel on Fitzalan Square in Sheffield, and I used to go down there when the pub was closed, playing snooker with young Charlie [his son]. And we used to come on holidays together [to Blackpool]. Uncle Charlie used to bring us in his car and take us back home again. When he retired he moved to Blackpool [more specifically, to Thornton Cleveleys], to West Drive. Uncle Harry had a pub in Rotherham. But he came to live in Blackpool as well. The whole family came here eventually, I think.

- [xxxvii] According to the website Sheffield History (www.sheffieldhistory.co.uk) the

Electra Palace, opened in 1911, changed to the News Theatre in 1945, the

Cartoon Cinema in 1959, and the Classic in 1962. It closed as a cinema in 1982 and was destroyed by a fire in 1984.

[xxxviii] The epic religious drama film Ben Hur was released in November 1959, and perhaps seen by me in 1960.

[xxxix] The film Exodus was indeed of epic length, but it was about the founding of the modern state of Israel. It was released in December 1960; and since our visits to Sheffield were in summer, this event presumably occurred in 1961.

[xl] Chris Woodhead wrote in a letter to me on

Friday 8th April

1966:

-

- I hitch-hiked over [to Grimsby] on Thursday and

came through Sheffield. I came right through

the city so I couldn’t resist paying a visit

to the bogs in Fitzallan [sic] Square.

One of the helmets smells of “wee”

42. On the left wall of the entrance hall at 12 Lees Hall Road, the wall adjoining Nos. 12 and 10, there was a row of coat hooks. When riding on the motorbike, my Dad and the pillion rider each wore a black, peaked helmet with a cork lining, and goggles; and when they went indoors, they would put the helmets on the floor under the coats hanging on the wall, with the top of the helmet on the floor and the open part upwards — upwards, that is, until on one occasion, just as we were about to set out, one of the helmets felt wet inside. As the only possible — not “possible”, anyone could have done it:

likely — suspect, Bobby got the blame for it. And despite being thoroughly wiped with a soaked, soapy cloth, forever after that the helmet had the sour smell of “wee”.

An example of the type of helmet that my Dad and the pillion rider wore

Retractile testes

43. I was in our bedroom at 12 Lees Hall Road on one of the later visits to Sheffield, and I noticed that the scrotum was empty. A feeling of panic swam over me, somewhat relieved by the fact that pressing the pubic area by hand brought the testes back down where they should be. But there remained a tendency for them to go back up gain. I wouldn’t normally talk to my Mum about my “intimate” anatomy, but on this occasion I was anxious enough to do so: “You know those ball things…” Anyway, when we got back home I was taken to Dr. Wylie’s. I can’t remember whether I saw Dr. Wylie or Dr. Glover, but whichever one it was told me not to worry, but come back if they went up and I couldn’t get them back down again. That never happened.

Steve gets Bell’s palsy

44. One day, our Steve found that he couldn’t move one side of his face, or could hardly do so. He went or was taken to Dr. Wylie’s, and was told it was “Bell’s palsy”. It was thought to have been caused by prolonged exposure to cold while riding pillion on the motorbike and sidecar. I can’t remember how long it lasted, but I do know that he recovered. Nor do I have any memory of riding pillion in his place, which I suppose must have happened.

“Dr. Wylie’s”, right, latterly Rushland’s Hotel, Thornton. The extensions to the back of the building are later additions.

Imagery © 2019 Google, Data SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, Landsat / Copernicus, Map data © 2019 Google

Other memories from the motorbike and sidecar days

AA and RAC boxes

45. The Automobile Association (AA) and the Royal Automobile Club (RAC) used to have roadside “sentry boxes” equipped with a telephone, allowing members to make contact with patrols in case of vehicle breakdown and to make emergency calls. I think there was an example of each, at different locations along the “very familiar” A586 road of

par.11. My Dad was a member of the RAC, and had a metal “RAC” badge mounted on the front of the motorbike. Did he ever have to use a “sentry box”? I can’t remember.

Perhaps the reason for their coming to mind is that the other I-Spy book, of the two I remembered in connection with Bakewell

(par.28), was indeed №10, “On the Road”, and that such boxes were listed in it.

Communication

46. Because of the noise of the motorcycle engine, and because the helmet straps included flaps which covered the ears, conversation with the driver was impossible. The

Busmar sidecar had a quarter light in the middle window on the side next to the driver, through which instructions and requests could be shouted.

If Mum thought that Dad was going too fast, she might call out, “Slow down, George!” This came from a television advert for

TV Times, the ITV programmes listings magazine; it was a cartoon depicting a family in a car.

- Wife (urgently): Faster, George, that programme starts at 6.15!

Grandma (slowly): Slow down, George, it doesn’t start till 7.20!

Children (popping up and screeching): Quick, Dad, it’s on now!

The scene changed from the car to their arrival home, as the words “The End” appeared on the TV screen, and showers of tears sprang from the faces of the two distraught children. Over this, played the jingle:

- ♫ Don’t forget the TV Times, ♫

♫ Don’t forget the TV Times, ♫

♫ The only way to see ♫

♫ What’s coming on ITV ♫

♫ Is to go and get the TV Times. ♫

If Mum and I needed a comfort stop, we might sing very loudly, to the tune of

The Keel Row:

- ♫ O, we want a wee-wee, ♫

♫ A wee-wee, a wee-wee, ♫

♫ We want a wee-wee,… ♫

I can’t remember the words we used for the last line of this refrain.

Singing

47. Mum and I would also sing songs for our own amusement, and these would sometimes be hymns that I’d heard in the morning assembly at school, or perhaps in the “church” part of the Sunday School

session.[xli] My Mum and Dad, though nominally Christian, didn’t go to church; but I think Mum remembered some of the hymns from her school assemblies. One of them

was:[xlii]

- Summer suns are glowing

Over land and sea

Happy light is flowing,

Bountiful and free.

Everything rejoices

In the mellow rays;

All earth's thousand voices

Swell the psalm of praise.

God's free mercy streameth

Over all the world,

And His banner gleameth,

Everywhere unfurled.

Broad, and deep, and glorious,

As the heaven above,

Shines in might victorious

His eternal love.

Lord, upon our blindness

Thy pure radiance pour;

For Thy loving-kindness

Make us love Thee more.

And when clouds are drifting

Dark across our sky,

Then, the veil uplifting,

Father, be Thou nigh.

We will never doubt Thee.

Though Thou veil Thy light;

Life is dark without Thee,

Death with Thee is bright.

Light of Light, shine o'er us

On our pilgrim way;

Go Thou still before us

To the endless day.

I don’t recall how many verses we remembered the words of, when we sang it.

- [xli] Sunday School, par.3

“Summer suns are glowing”, as it appears in the old, familiar, square Methodist Hymn Book that was used at Wignall Memorial Methodist Church, where I went to Sunday School

[xlii] To the tune “Ruth”, composed in 1865 by Samuel Smith (1821–1917)

Picnic stoves

48. My Dad bought a couple of tinplate cylindrical picnic stoves. They looked like paint tins with holes in the sides, with lids like paint-tin lids that were prised off with a screwdriver or more likely a spoon handle. Inside each was a burner, in the form of a smaller metal cylinder, open at the top, with holes in the rim. You poured methylated spirits into this, and lit it. Initially there’d be just a flame, almost invisible, hovering over the pool of liquid; but when the burner got hot, blue flames would start to come out of the holes, just like they did from a domestic gas-cooker burner. There was also a metal cover that fitted over the burner, to act as a snuffer to put the flames out. He also bought a little tinplate kettle, and a small saucepan and frying pan, perhaps with folding or detachable handles. So we were equipped, on days out, to make a pot of tea and so not have to take a Thermos flask with us, and to heat baked beans and fry some bacon, if we weren’t in a position, or weren’t inclined, to go to a café on our

travels.[xliii]

- [xliii] For what happened to these picnic stoves, see The “Abortive Camping Expedition” — Day One, pars. 5 and

6.

|